TURNING VISION LOSS INTO A MEANS FOR ADVOCACY

“Back when the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) was passed in the 1990s, I had no idea how much of an effect it would have on me today. I believe it’s my responsibility to educate building professionals on the code’s intent and help them empathize with those who aren’t so fortunate.”

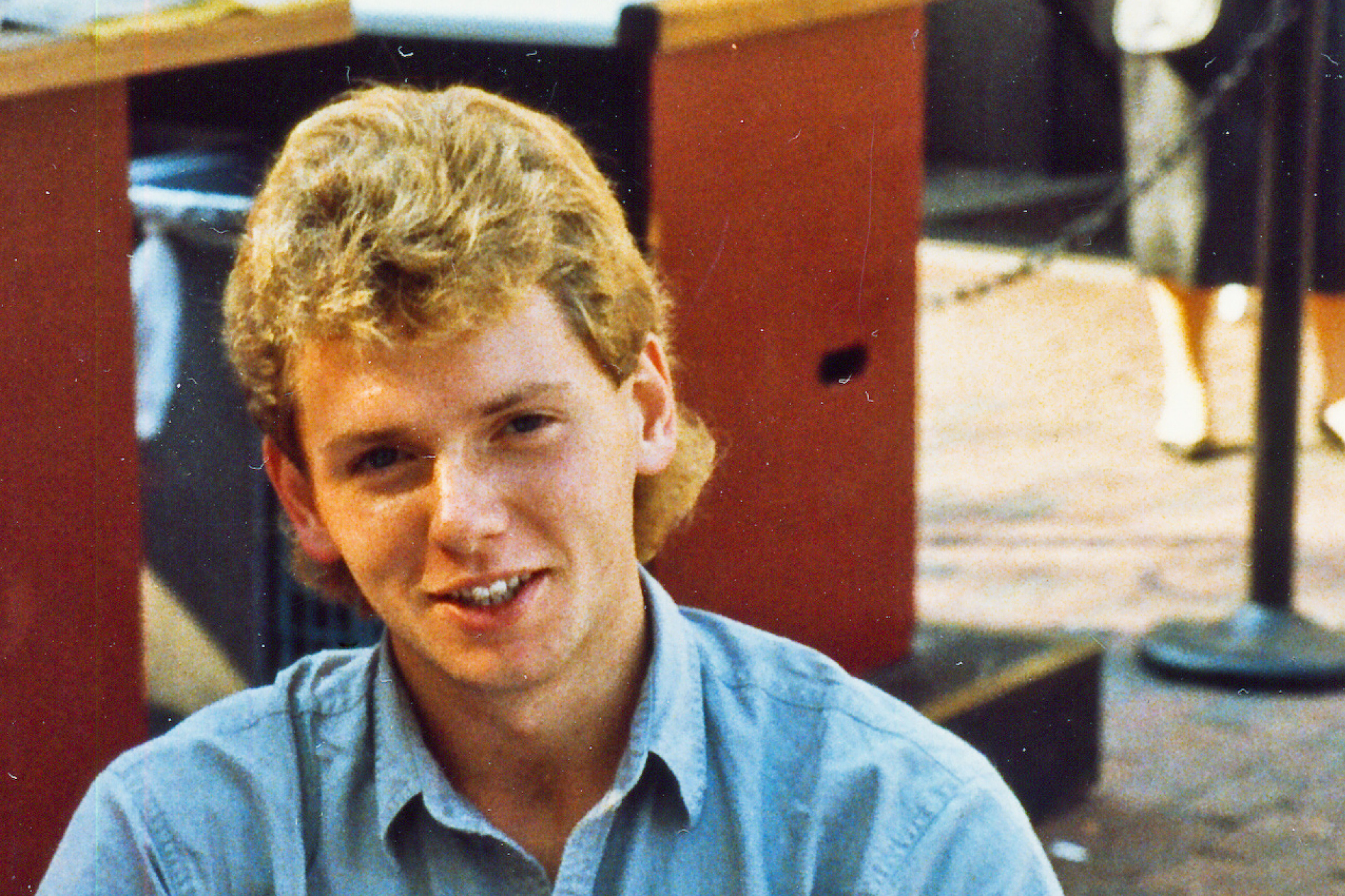

We recently sat down with our very own Rick Dahlstrom, Project Manager and Senior Architect here at MSKTD, who is in the process of losing his sight. Here, Rick shares how his appreciation of ADA building codes has changed as his vision loss has progressed, and he offers insights into ways we can all become advocates—not just for the visually impaired, but also for people dealing with a wide range of health conditions or physical impairments.

LET’S TALK ABOUT YOUR VISION. YOU ARE IN THE PROCESS OF LOSING YOUR SIGHT. TELL US ABOUT THE DIAGNOSIS, WHEN YOU RECEIVED IT, AND HOW IT IMPACTS YOUR VISION.

Rick: It’s a genetic disease. I’ve known about it since I was 8 years old. I have one bad gene, and that set everything off. In my case, it affects the rods, but my cones are intact. That means that I have very little peripheral vision. I’ve lost my night vision, and my color acuity is slipping as well. But overall, I can see 20/40 with correction in my central vision.

HOW HAS THAT CONDITION IMPACTED YOUR WORK AS AN ARCHITECT?

Rick: I’ve worked at MSKTD for 32 years, so I’ve built up a lot of experience working on projects of all scales, large and small. That’s knowledge I can use, even though I don’t go to job sites anymore. I’m considered legally blind, but I can see in my head what other sighted designers don’t. I can integrate aesthetics with functionality, sustainability, engineering and programming. These are the things that are essential for an architect. I also use my depth of experience to mentor younger architects. In that sense, my lack of ability to be out on site has created an opportunity for me to mentor up and coming architects.

HOW HAS THE FIRM SUPPORTED YOU THROUGH YOUR VISION LOSS PROGRESSION?

Rick: I’m in a unique position as the only legally blind architect in the office. My role as a project manager encompasses anything and everything related to a project. I’ve had to back off from some of those responsibilities, but the team is there to accommodate me. One way MSKTD has offered support is by getting me the technology I need to do my job, such as two larger monitors that allow me to perform at a high level even while working with lower resolution images. That was a big deal for me since Revit software is not designed for those with low vision.

My co-workers look after me when they know I need help. I am grateful for their understanding and assistance. This is part of the reason why MSKTD is a great place to work. We all have our shortcomings and strengths. There is nothing to be embarrassed about. At the same time MSKTD is “leveraging” all of our strengths to meet our clients’ needs.

YOU SERVED IN LEADERSHIP AT FOUNDATION FIGHTING BLINDNESS. WHEN DID YOU GET INVOLVED, AND HOW HAS MSKTD SUPPORTED YOU IN THAT MISSION?

Rick: As of last year, I had spent 16 years as the president of the Fort Wayne chapter of the Foundation Fighting Blindness, which has 50 chapters across the country. I was involved in fundraising with them and helped them raise close to a million dollars. The Foundation Fighting Blindness hosts a VisionWalk every year, and I always received a lot of support from the team here at MSKTD, both associates and partners. They really opened up their minds and their wallets. They had a lot of empathy for the challenges I was facing, and I greatly appreciated it.

YOU ARE CURRENTLY WORKING WITH THE LEAGUE, WHOSE MISSION IS TO “PROVIDE AND PROMOTE OPPORTUNITIES THAT EMPOWER PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES TO ACHIEVE THEIR POTENTIAL.” HOW HAS YOUR WORK AS AN ARCHITECT INFORMED YOUR WORK THERE?

Rick: In my work with the Foundation Fighting Blindness (Fort Wayne Chapter), I met others with disabilities. Some of my connections there also work at The League. Last year, they launched a new program to develop advocates for people with any disability. Eight months of taking classes really opened my eyes to the many different disabilities people in our community face.

In my projects, I already accommodate for people with disabilities in the built environment. I have expanded that thinking to apply to aging and how we will all navigate some level of disability for ourselves or our loved ones. It has also made me realize there are just as many government policy hurdles as there are physical ones. Through my collective experience, I want to help eliminate those barriers.

TELL US ABOUT THE ADA AND HOW YOU HAVE COME TO APPRECIATE IT IN A NEW WAY AS YOU FACE VISION LOSS.

Rick: Back when the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) was passed in the 1990s, I had no idea how much of an effect it would have on me today. I’ve come to understand that being disabled is more than wheelchairs. I believe it’s my responsibility to educate building professionals on the code’s intent and help them empathize with all of those who are using the space.

Now that I’m more dependent on the accommodations in the building code, I understand the reasons behind them. For instance, ADA requires contrasting nosing on a stair. Aesthetically, I didn’t like the look of a stripe on the stair design. Now I understand that people with vision loss have trouble differentiating changes in elevation without that contrast.

It’s been very interesting. In the 1990s, I didn’t understand why you needed accommodations such as level sidewalks or zero curb. It all comes around. I’ve gotten to the point where I like to have something to hang onto when I’m navigating the stairs. There’s even a rhythm on a stair. Once you start getting past an 11-inch tread and a 7-inch riser, you create an extra deep ledge, and that’s not a natural gait. We want to seek to understand and find solutions that work. We don’t want to create unnecessary issues for people. Unless you experience it, you may not know the reason behind the decisions made.

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE LOOK LIKE FOR YOU?

Rick: The staff here has been great. They physically look out for me. If I’m not looking directly at something, I’m not seeing it. They’ll let me know if there’s an obstruction. A number of people help me navigate going from light to dark environments when we go out for lunch. There’s really nothing negative about coming to work for me, and I am in the process of a pivot in my perspective. I realize that there are people who are worse off than I am. They need someone to look out for them, too.